A monocle is a single eyeglass kept in position by the muscles around the eye. The same can be said of Monocle magazine, a publication fixated on how cities should all be built in style and for conspicuous consumption.

Since launching in 2007, this publication by journalist-turned-media entrepreneur Tyler Brûlé has become a celebrated design bible for urban planners and the elite. Before Monocle, creating an attractive city worth living in never seemed so simple and stylish.

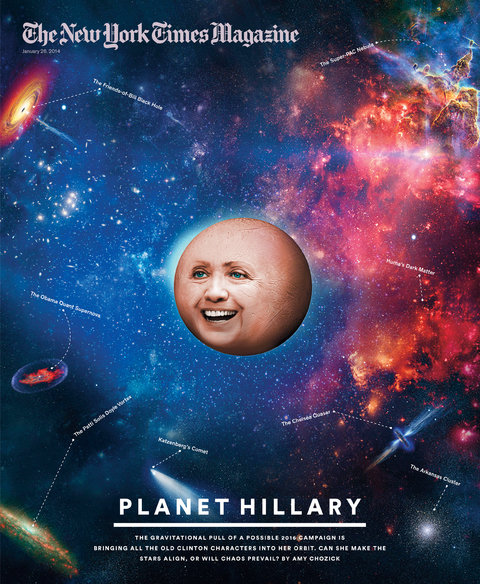

From its format down to design and content, Monocle smoothens over the complex subject of urbanism in a smart and attractive-looking publication. It’s Brûlé’s vision of a cross between the The Economist and GQ, a perfect status accessory for the modern executive—best displayed when one is dressed in tailored suits and leather shoes.

Monocle calls itself “A briefing on global affairs, business, culture & design”, but each issue reads more like Brûlé’s personal travel blog (he is known to travel more than 250 days in a year) printed on uncoated stock — all 300 pages of it, including booklet inserts and advertisements. A glossy spirit of optimism pervades throughout this magazine stuffed with informative blurbs, clever lists, one-page profiles, as well as question-and-answer interviews. Whether it is a survey on the world’s most livable cities, an interview with a politician or a shopkeeper, or an advertorial on Samsung’s latest phone, there is little difference. Everyone and everything on Monocle is selling their suggestions in creating a better city. Nothing seems problematic, not even the fact that almost everything Monocle features as good examples of city living are unaffordable to the rest of the 99%.

Despite its marketing stance, Monocle tries to look like it is delivering on its promise of “quality journalism” through design and art direction. Its commissioned photography borrow the visual language of objectivity, while its illustrations project a sense of simplicity. Documentary style photos of places run alongside straight-up style portraits of business owners, shops and products, creating a veneer of honesty over the fact that Monocle is promoting them to readers. Many of the magazine’s illustrations of city life display a charming LEGO-like simplicity, rendered in a uncomplicated style of elemental forms reminiscent of Isotype. Like this international picture language, Monocle’s illustrations smoothen out differences and diversity within and across cities, falling back on outmoded national costumes and stereotypes to fit a trans-national universe the magazine is building. From page to page, the images and short texts are packed into a three-column grid creating a sense of sameness regardless of who, what or where, which only encourages reader to skim rather than read seriously.

Most telling of Monocle’s journalistic aspirations is the typeface the magazine and brand has chosen to be set in: Plantin. The magazine’s creative director Richard Spencer Powell wanted a nod to “old journalistic values”, and this early 20th century typeface also gives the brand instant tradition, reinforcing why Brûlé had picked the archaic object of the monocle as its name. Despite establishing such origins, Monocle is uninterested in practicing journalism the old school way. The profession’s cardinal rule of separating editorial from advertising is discarded because Brûlé once said that “all good journalists are good salespeople too”, and Monocle’s editors often accompany ad directors to sales calls. It shows. This magazine’s advertorials are difficult to distinguish from editorial content. The only indication is a “(Brand name) X MONOCLE” tag at the bottom of the page, an ambiguous line that could also read as endorsed by Monocle.

But this magazine has no qualms about mixing the two. It is good business for Brûlé, who is also chairman of the branding and design agency, Winkreative. Monocle is a great advertising platform for the agency, as editorial subjects such as the government of Thailand have become clients too. In Monocle, Brûlé has created a marketing darling that has been recognized by Advertising Age which awarded him “Editor of the Year” in 2011, as well as, Adweek which named Monocle the “Best brand for living the good life” in 2012.

This commercial success is undoubtedly Monocle’s great achievement in a print media industry puzzling over how to survive in the digital age and has made it a model for many publications to follow since. But it comes at a cost: real quality journalism that helps us understand cities as citizens and not just consumers. Unlike those who live in Monocle city, these are ideals most of us cannot afford to buy nor lose.

———–

Written for Rick Poynor’s Critical Takedown workshop at D-Crit. This essay was later published on Design Observer.