Architecture or property are different names for what most of us call a building.

But the emergence of starchitects has blurred the line between the two. Nowadays, there are buildings, and there are buildings designed by famous architects.

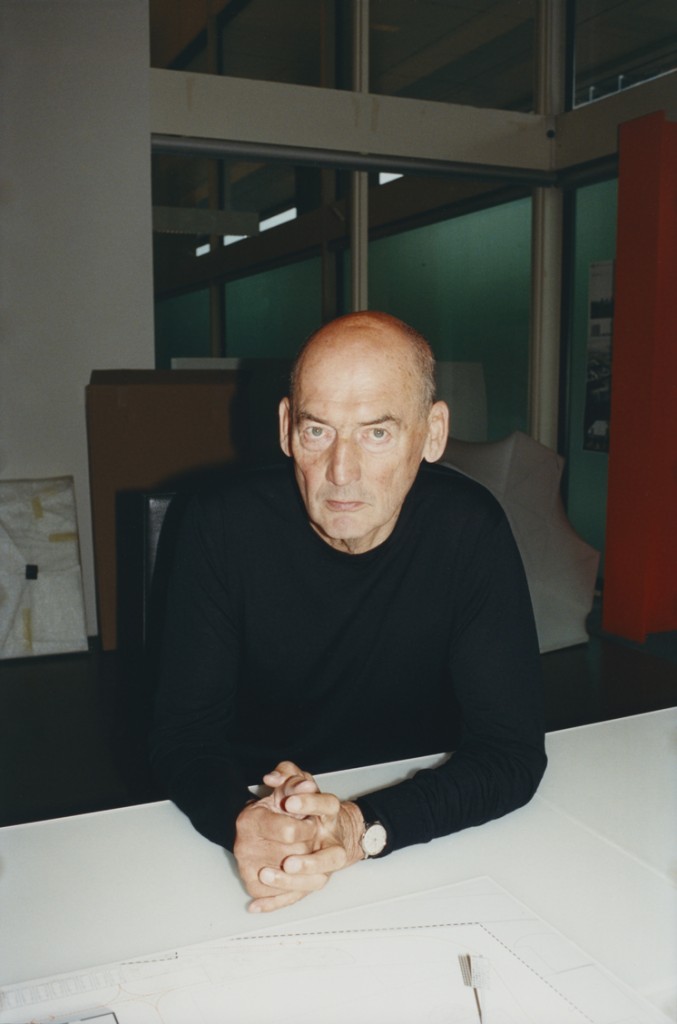

The city of Singapore has recently become the home of several condominium towers designed by starchitects such as Rem Koolhaas (The Interlace), Zaha Hadid (D’Leedon) and Jean Nouvel (Le Nouvel Ardmore). Local developers seem to believe that such architects renowned for their avant-garde designs can raise the values of their properties with a touch of designer class.

But what happens when such avant-garde architects meet the property market? Imagine Koolhaas or Hadid selling their architecture to the man on the street. You can’t — that’s the job of real estate agents. And the translation of these architects’ often abstract concepts into market language reveal the gaps between architecture and property.

Consider Moshie Safdie’s Sky Habitat, which became famous as the most expensive suburban condominium in Singapore when it was first launched in 2012.

This is how the project is introduced on a dreary grey backdrop with no photos on Safdie Architects website:

“Over the last four decades, Safdie Architects has created from the experimental project Habitat ’67 in Montreal a series of projects incorporating fractal-geometry surface patterns, a dramatic stepping of the structure that results in a network of gardens open to the sky, and streets that interconnect and bridge community gardens in the air.”

The developer’s website for potential buyers, however, begins like this:

This is just one of several blurbs including “Garden Living from Above” or “Dive into Our Sky Pool” that markets the “sky life” created by Safdie’s design. Selling such a view seems a strategic move considering the apartments are marketed to middle-class Singaporeans who are clueless about Safdie (“also known as ‘Who?’ to 99% of Singaporeans,” said one commentator). They would be familiar with his Marina Bay Sands design, however, a building which introduced the concept of a pool in the sky in a big way to Singaporeans.

Absent from the “sky life” hype, however, are how Safdie’s design attempts to foster a sense of the public amongst its residents with “generous community gardens and outdoor spaces on the ground”, according to the architect’s website. The developer’s descriptions of the design never expand beyond “you” and “your family”, highlighting how architecture is massaged into private property.

This struggle between architecture and property also surfaced in a recent Icon interview with Safide when he revealed that a woman wrote to him for help in getting a loan to buy a Sky Habitat apartment.

“When you take land and construction prices and the costs developers add on, it’s a struggle between affordability and the ideal. Moreover, the development was so desirable when it was built that it immediately became gentrified,” he said.

———–

Written for Elizabeth Spiers and Chappell Elison’s Online Publishing class at D-Crit.