Giuseppe Lignano has no architect friends. When not at work, the founding partner of architecture firm LOT-EK would rather hang out with people outside the industry instead.

School teachers, businessmen, chefs and even housewives — his love for meeting people from diverse backgrounds and cultures mirrors the industrial bricolage his studio has become famous for. While most architecture firms design buildings to be made of glass, concrete and steel, LOT-EK has used kitchen sinks as cabinets, petroleum trailer tanks as bedrooms, and stainless steel truck bodies as homes. Over the last two decades, the studio Lignano started with his long-time collaborator, Ada Tolla, has been turning non-traditional architecture elements into standout designs.

“I like to be more of an outsider in everything I do,” says Lignano, looking smart in a fitting blue shirt and dark denim jeans. Even the clothes on the 50-year-old reflect how the gay man has always seen himself outside of New York city’s straight “white-male dominated” architecture industry with “their all black outfits”.

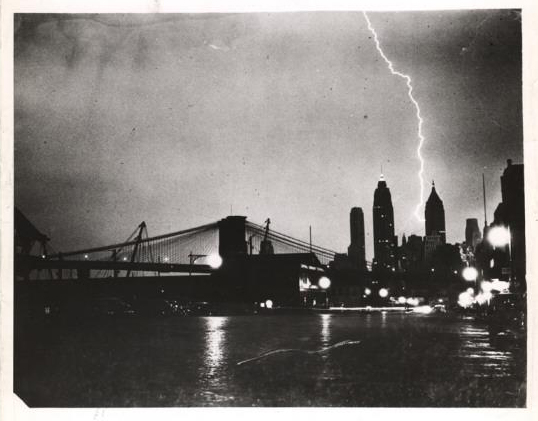

Lignano first came to the United States with Tolla after they graduated from architecture school in Italy. Bowled over by how modern New York was compared to their hometown in Naples, the duo moved to Manhattan for a postgraduate fellowship at Columbia University in 1990. Three years later, they set up LOT-EK to pursue their fascination with the city’s industrial landscape, which has defined their design vocabulary ever since.

Fire escapes, airplane fuselages, steel ducts and other detritus of the industrialized society are examples of the “Roman aqueduct now seen in the making,” says Lignano, proof of how we live today when archaeologists dig up the ground in 2,000 years time. But rather than leave them to waste till then, he sees the perfect building blocks for design.

“As a civilization, we would feel much less guilty if we had the ability of looking at what we make with enthusiasm and say we could do this with this, instead of just freaking out that we are accumulating millions of containers,” he says. “I think it would be a great thing, a really beautiful thing not only in architecture.”

This palpable love for human creativity — measured by his distinct left eyebrow that arches upwards whenever the grey bearded Lignano speaks excitedly — can be traced back to when he decided to become an architect. Barely ten years old, he had visited his uncle’s newly renovated apartment, and was blown away by how the architect had transformed the space. Uncle Franco became a huge inspiration in Lignano’s pursuit of wild and imaginative designs, which went so far that even the mentor said his nephew’s works were “completely crazy” and unacceptable to the world.

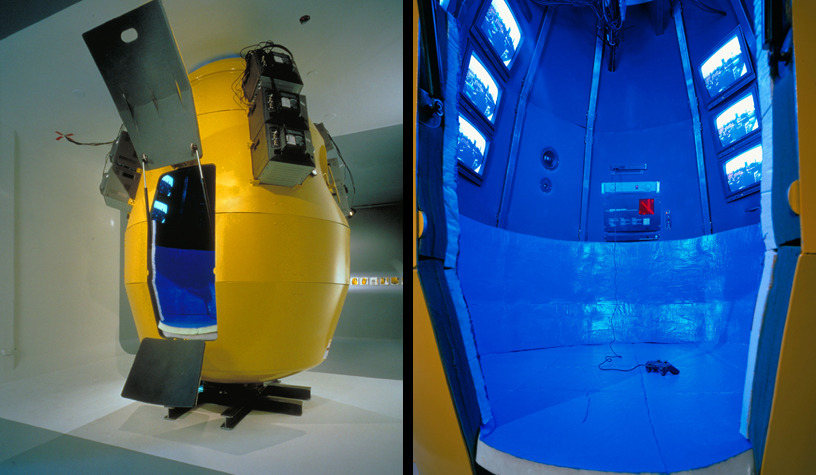

From turning an airplane container cargo into a personal workstation and using a cement mixer as a cocoon for watching television and playing video games, LOT-EK has gone from designing such installations for art galleries and museums to building architecture, most notably with the shipping container. The studio has converted them into mobile retail stores for PUMA and Uniqlo and will be inserting into New York’s Pier 57 some four-levels of containers filled with — not goods, but — a market, restaurants, and studios for artisan businesses that will turn the former shipping hub into a cultural and civic center.

More recently, LOT-EK has also gone beyond repurposing the shipping container to building with them. Lining one side of its container-like second-floor studio along Chrystie Street are various architecture models that are as arresting as the neon yellow and grey interiors. What looks like New York’s winding Guggenheim museum turned on its side is a proposal for a public library design consisting of 170 containers sliced, carved and stacked to create seven wheel-like structures joined together. Another model resembling a floating spaceship is actually an art school built in South Korea where LOT-EK sheared eight containers along a 45-degree angle, assembled them in a fishbone pattern, and elevated the entire structure.

These works are more than just futuristic-looking. Lignano takes down each model to explain how LOT-EK is “creating space by removal,” working like “skillful butchers” to cut open rectangular containers to different shapes, and combining them to make out-of-the-box buildings and spaces. This radical approach has gained LOT-EK media attention and helped it win prizes, including being a finalist for the National Design Awards in 2008. But up till today, the studio still struggles to get clients.

“A lot of people that have started much later than us have completely gone so much more than we have from a business point of view,” says Lignano. “The hardest part has been the fact that there is a lot of people they call because they think this is a very cheap way of building. So in a way they call for the wrong reasons. Because we don’t do this because it is cheap, we do this because it is smart for what it is.”

But beyond an ecologically smart way of design, or what it now markets as “upcycling,” Lignano believes in his approach because of how creative it is. It is what has kept him going for so long despite the lack of major commercial success until recently. This belief has helped LOT-EK grow from just Tolla and him working by day and waiting tables at night, to a team of 15 now serving clients in the US, Holland, Japan and China.

In that twenty years, New York city has also grown up as polished skyscrapers now overshadow its once chaotic industrial landscape. Even as his sources of inspiration are cleaned up, Lignano sees opportunities for LOT-EK’s works which has “more grit, more personality,” unlike the “boring” New York architecture scene which he likens to Wall Street.

In this sense, Lignano is no outsider. LOT-EK’s diverse, layered and a little rough around the edges architecture is exactly what New York city is — once you’re on the inside.

———–

Written for Adam Levy’s Art of the Interview class at D-Crit.