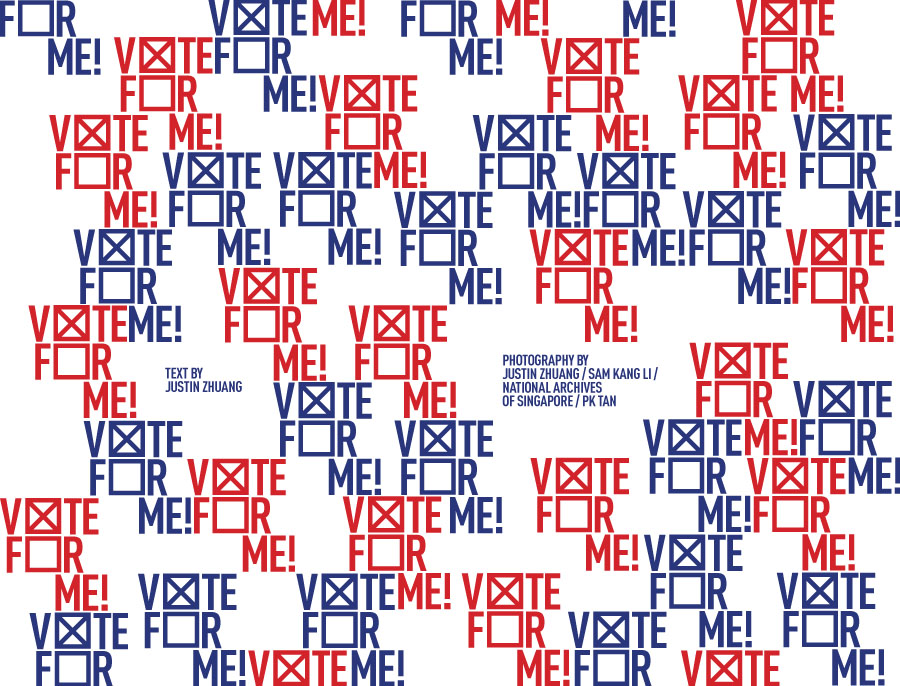

Singapore’s 11th General Elections since independence marks the beginning of a design-conscious politics—a 2011 essay I wrote for The Design Society Journal No. 03.

The day after Nicole Seah was officially presented as an election candidate for the National Solidarity Party (NSP), The New Paper asked on its cover: “Do looks matter in elections?” It was directed at the online buzz generated after the 24 year-old Seah first announced over Facebook that she was standing for elections. Netizens were clearly taken in by her profile picture—what the paper described as “lovely flowing hair, make-up and her good side showing”—so much so that nobody bothered who she was contesting with in Marine Parade Group Representation Constituency (GRC). Some even began dubbing NSP as the “Nicole Seah Party”. Soon, digitally edited pictures of her as Wonder Woman and Scarlett in the upcoming G.I. Joe movie also began making their rounds online.

However, Seah, in her own words, was not just “another pretty face”. She was confident and articulate, making astute remarks during her campaign trail. This, plus her good looks, projected the image of an attractive and credible candidate to voters. Just over a fortnight after starting her Facebook page, Seah received even more ‘Likes’ than the nation’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew, earning her the title of Singapore’s most popular politician. Despite this, her NSP team did not win the election battle at Marine Parade. Yet, by garnering so much attention and winning 43.36 per cent of the votes against a People’s Action Party team led by former prime minister Goh Chok Tong, Seah’s campaign demonstrated how image played a part in helping a young unknown like her win votes.

This echoes the 2008 presidential election in the United States, when a relatively newcomer Barack Obama “crafted a meticulous visual strategy”, that helped propel him to victory. While Seah and the other candidates of Singapore’s 11th General Election did not display the sophistication of Obama’s visual campaign—right down to choosing an appropriate typeface—they produced one of the most visually-driven election in recent Singapore history, heralding the beginnings of Obama-style politics in the future.