The now-defunct Baharuddin Vocational Institute was Singapore’s first formal school for design. Justin Zhuang looks at how the institute laid the foundation for the design industry here.

The now-defunct Baharuddin Vocational Institute was Singapore’s first formal school for design. Justin Zhuang looks at how the institute laid the foundation for the design industry here.

Category: History

From International to National: A Singapore Design Journey

International, trendy and a blend of east meets west. Graphic design in Singapore is often viewed as indistinct and an inevitable outcome of its physical constraints. But scratch beneath its surface and one is surprised by how much of it is by design like much of the city-state. While the tropical island is exposed to global economic, social and cultural tides, Singapore has developed a graphic design industry on its terms just as it has reclaimed land from the sea to redefine its geography.

As a port city dating back to the 13th century, Singapore has long had a need to support its commerce with graphic design. However, its modern expressions emerged only after the British established a trading post at the mouth of the Singapore River in 1819. It began attracting an influx of immigrants from China, India and Europe to live and work alongside the native Malays. Singapore’s development into a thriving emporium in the 20th century saw the rise of various trades including the “commercial artist”, the precursor to the graphic designer. These individuals with artistic flair were typically Chinese, who made up three-quarters of the population by then, and they toiled in advertising houses owned by the Europeans who dictated prevailing styles.

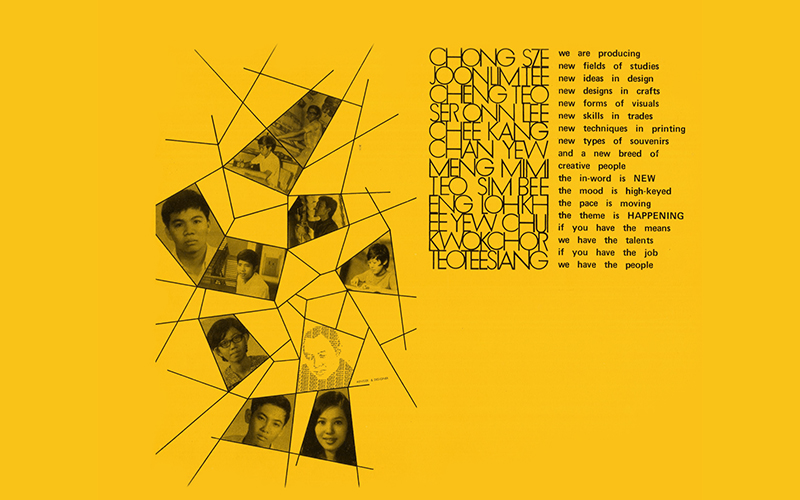

Although commercial artists formed the Singapore Art Advertisement Institution as early as 1937, the profession only became prominent some three decades later. In the 1960s, the locally-elected government embarked on an industrialisation drive to secure Singapore’s economic independence as it marched towards independence. Design became part of a national policy to improve Made in Singapore goods, and the Baharuddin Vocational Institute was started to train local designers. “The reason for this Institute is that we have reached that stage of industrialisation requiring greater focus on design…,” declared Member of Parliament Wong Lin Ken at its official opening in 1971. “In this way, our Republic will some day be able to depend entirely on our own designers and craftsmen.”

Until then, design for a nascent nation fell to foreigners and a small number of overseas-trained locals. A pioneer graphic designer was William Lee who returned from London in 1969 to start Central Design. An early client was the newly formed Singapore Airlines, which became a national icon. While American consultants Walter Landor designed the company’s logo and livery, Lee and his team fleshed out the collaterals for its launch in 1972. Over the next two decades, Central Design helped many local corporations adopt the International Style, including Shangri-La Hotel and United Overseas Land which still adorn his strikingly modern logos.

Lee’s generation successfully created the design consultant in Singapore, which was cemented by the founding of the Designers Association Singapore in 1985. The profession was further boosted in the nineties with a new national design drive, this time to turn Singapore into a global design hub. As the government wooed multinational design firms to open shop here, they also encouraged local designers to export their services. These efforts to “internationalise” Singapore design paid off in 1997 when the World Trade Organization adopted a logo by local design house Su Yeang Design as its official emblem.

The progress was disrupted by a string of crises—the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the 2000 dot-com bubble burst and the 2003 SARS epidemic—that wore down the old guard but opened up space for a new generation. Powered by Singapore’s early embrace of information technology, young designers now had desktop publishing to streamline the laborious design process, and broadband internet to explore new ideas and networks. A design studio was now as small as an individual with a computer in a bedroom. The liberation was expressed in a rejection of the drab corporate suits worn by the previous generation, in favour of T-shirts and sneakers which better expressed the designer as a personality. As William Chan, the co-founder of local art and design collective PHUNK explained at its 10-year retrospective in 2005: “When we started, people thought all graphic designers could do were design ‘Big Sale’ flyers and lay out text on posters. But these days, we are viewed as trend setters.”

Design’s new lifestyle function arose from Singapore’s efforts to regenerate its economy by attracting the “creative class”. Industrial manufacturing gave way to intellectual property, while cafes, museums and hip cultural venues sprouted out in the former cultural desert. In 2003, the government also formed the DesignSingapore Council, which nurtured young designers’ desire to go beyond servicing clients and venture into creating content and crossing disciplines. Amidst the flourishing of creativity in the 2010s, from indie magazines to design exhibitions, locally-inspired souvenirs ultimately captured the popular imagination of what “Singapore design” is—fuelled by the patriotic fever as Singapore celebrated its golden jubilee in 2015.

From going international to celebrating the hyper-local, Singapore graphic design has clearly grown more comfortable in its own skin with time. The Singapore designer today has one eye on the world and the other on home, and it is this ability to traverse the global and the local that perhaps best defines what “Singapore design” is.

➜ First published in Design Anthology, Asia Edition Issue 26