Just over two weeks ago, Straits Times launched Through the lens, a micro site that features the work of its photojournalists as well as the best pictures from around the world. Today, visuals and multimedia proliferate our world and have also become an integral part in telling the news. In recent years, the latest camera technology that combine photography and videography has also given rise to “multimedia storytelling” — the use of images and audio to present a story (But isn’t it still video?). More and more, photojournalism is no longer just about having a spread on the newspaper or a photo gallery online, and ST is not alone in doing this, The New York Time started its Lens blog over a year ago.

For me, what’s unique about Through the lens is its Flashback section. A media institution like the Straits Times probably holds the biggest archive of pictures of Singapore’s history, and it’s great to see it finally come to public light. Thus far, you can see what the National Stadium, Hong Lim Park, Miss Worlds, and even how flooding looked like in the past. These photos help to add historical context to some of the recent issues the print stories have brought up.

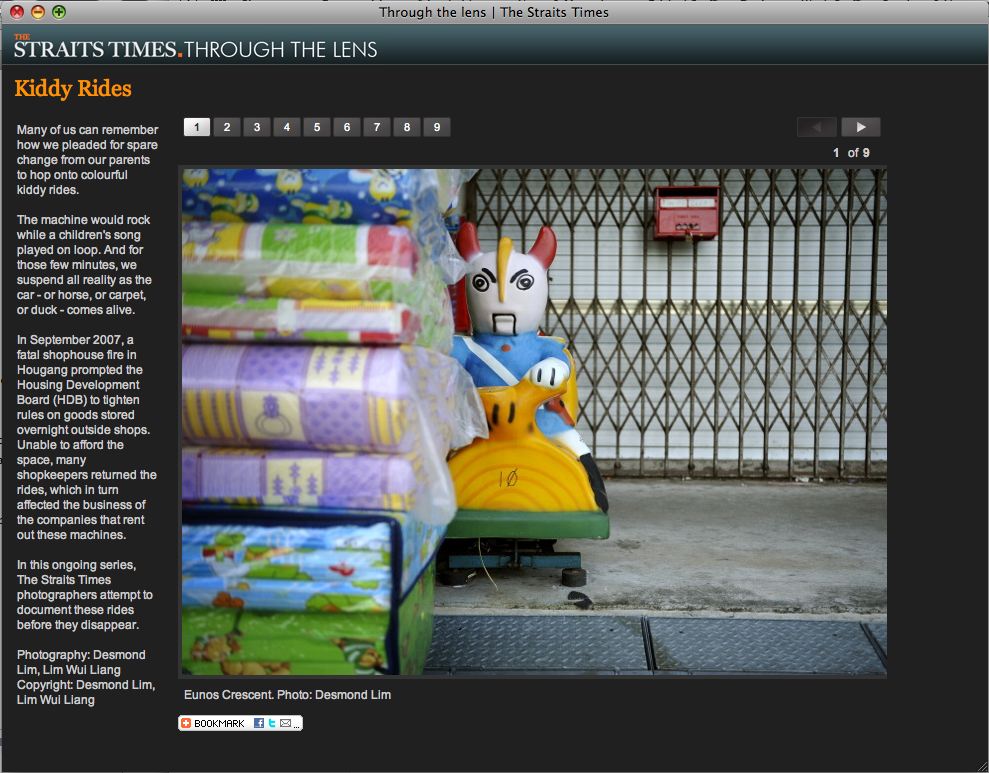

Through the lens is an important development for ST’s photojournalists. They have long been seen as sidekicks to the journalists who write the story, yet, people remember photos and are drawn to it first before even reading the news. This website finally gives ST’s photojournalists their own platform to showcase more of their photos, as many often do not make it to print. More importantly, it gives them their own voice to author their own stories. Many of the photo essays and multimedia currently up were done in conjunction with print stories. However, there are now some web-only and photo-only stories. One that caught my eye was Kiddy Rides, a on-going photo essay documenting the colourful machines that would rock children for a few minutes with music. These are gradually disappearing from Singapore after a 2007 shophouse fire in Hougang led to a tightening of rules on how spaces outside shops are used. This is a story that is definitely more interesting visually than in print and Through the lens and opens up an avenue for work-in-progress photo collections.

It’ll be interesting to see how Through the lens develops in the coming months. Will it be actually enhance the role of photojournalism in ST or become a container for the paper to keep photojournalism online? From what I understand, this site means more work on top of the daily assignments for the photojournalists, so it’s really a labour of love now more than anything that is keeping it alive currently.