An essay commissioned by the Goethe-Institut Singapore for the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore’s “IDEAS FEST 2016/17: CITIES FOR PEOPLE”.

Even before “creative”, “walkable”, “high-density”, and “liveable” became recent buzzwords for Singapore’s future as a city, architect William Lim Siew Wai had advocated for such a vision almost five decades ago.

As part of the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group (SPUR), a non-governmental think-tank a young Lim co-founded with other architects in the 1960s, they laid out “The Future of Asian Cities”—a visionary 1966 essay which reads like how Singapore now envisions to become.

“Imagine a city where…” work, play and living is mixed and concentrated, everything is connected by an efficient rapid transport system, and clean parks as well as open spaces are abound. Concerned about Asia and Singapore’s then rapidly growing population and massive industrialisation in the 1960s, SPUR dreamt up such “radical transformations” to modernise the region, but in a manner sensitive to the local way of life.

This was not the development path the Singapore government eventually chose, however, a divergence we can see in the city today. With the help of the United National Development Programme, the resulting Concept Plan 1971 resettled the population across neatly divided areas of singular function, all served by an island wide system of expressways—a Western model that has since proven inadequate for the Singapore of tomorrow.

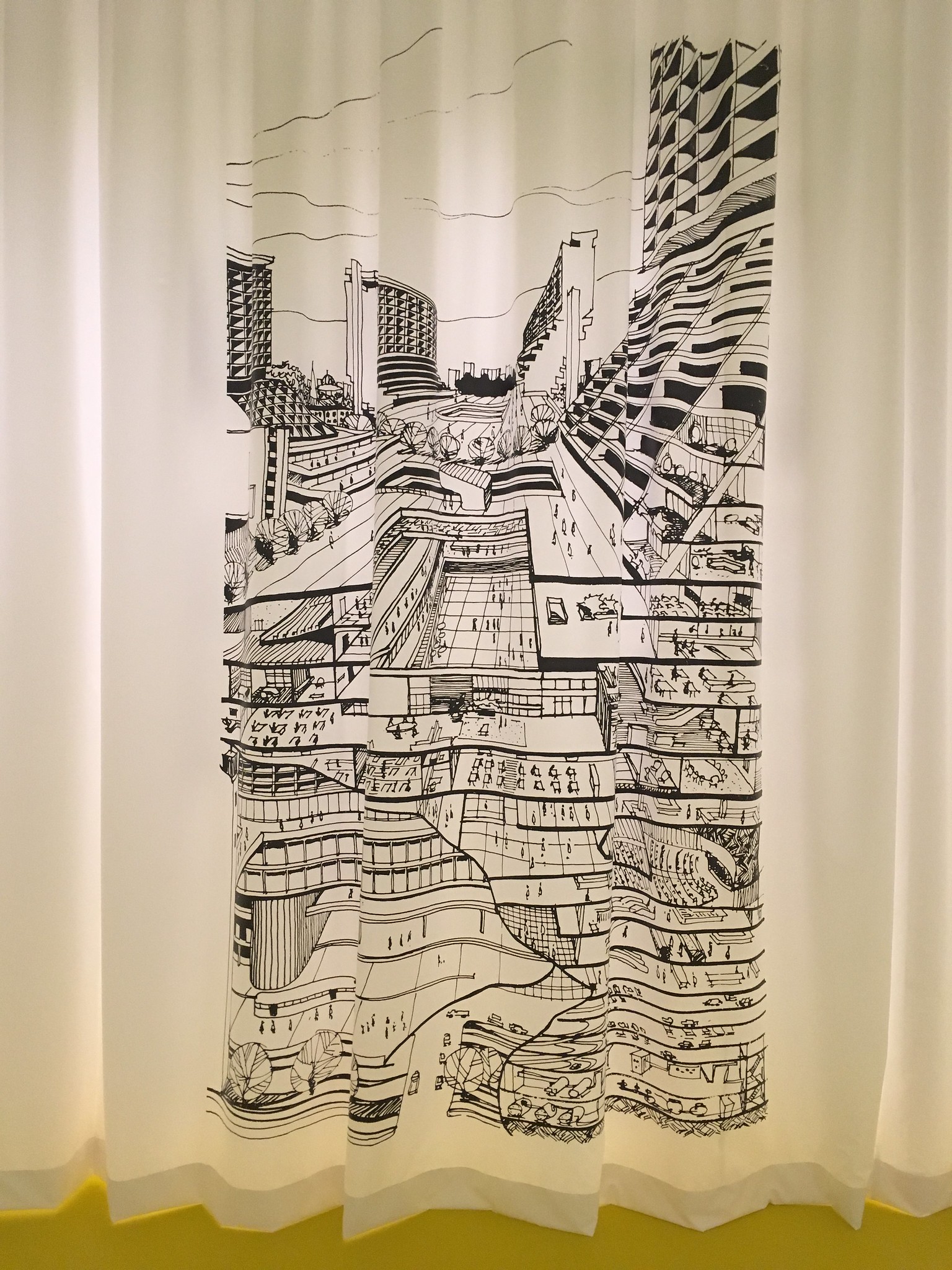

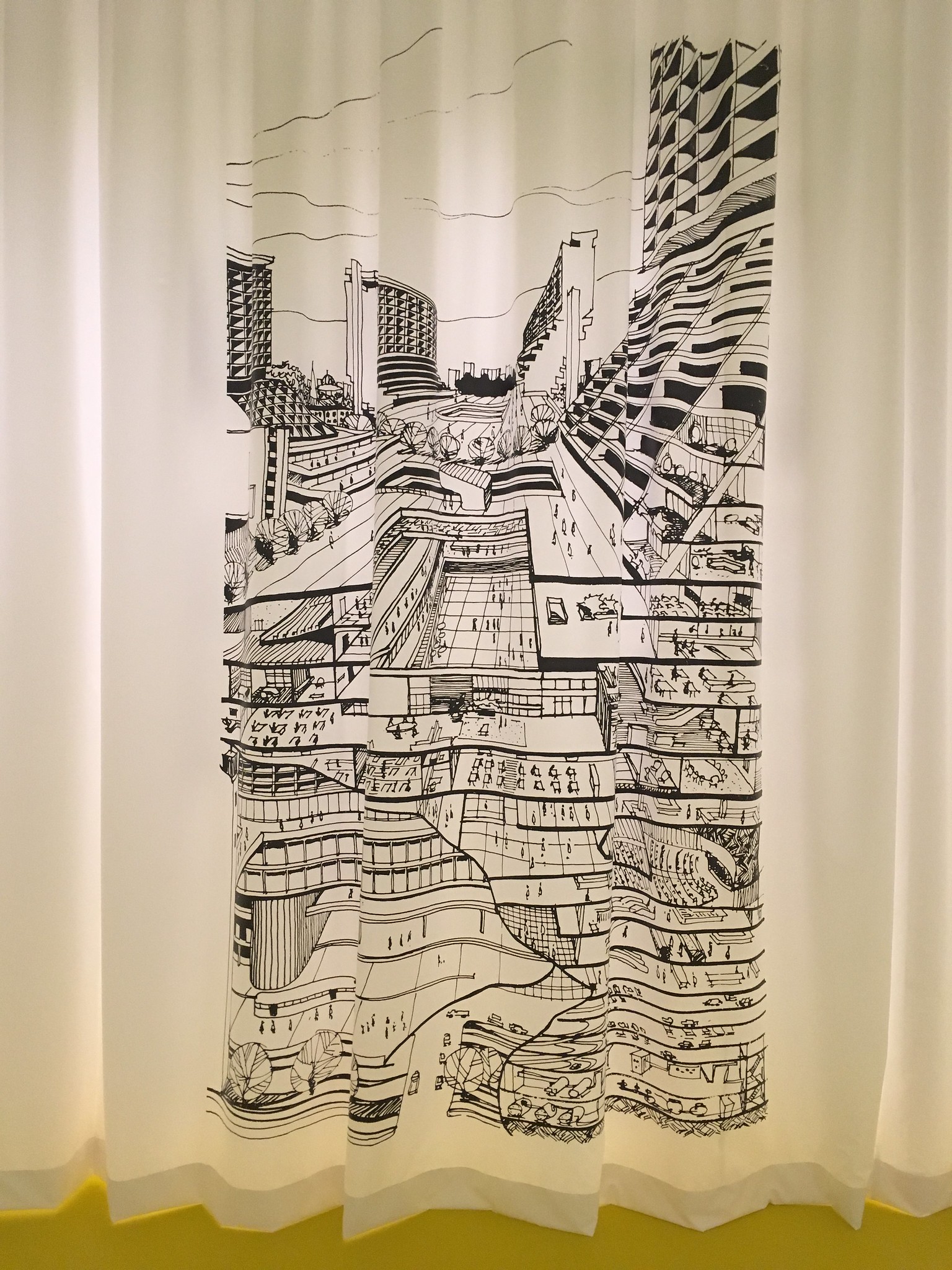

Despite the city’s rejection of his ideas (SPUR was dissolved in 1975 partly due to opposition from the government), Lim never stopped dreaming of a utopia of Cities for People, also the title of his 1990 book. As an architect, he helped design People’s Park Complex (1972) and Golden Mile Complex (known as Woh Hub Complex when it opened in 1974), two pioneering mixed-use developments where bustling street life defined its interiors. As an urban activist, Lim made a stand on the value of built heritage amidst a city then fervently razing everything old for the new. In 1982, he worked with poet and entrepreneur Goh Poh Seng to conceptualise Bu Ye Tian, a proposal for the conservation and adaptive reuse of Boat Quay. Two years later, he helped produce Pastel Portraits: Singapore’s Architectural Heritage, a book that sparked the city’s conservation movement.

Underpinning Lim’s architecture and advocacy are the many books he has authored and edited, an endeavour he is dedicated full-time to since retiring from practice in 2002. While his writings can be frustratingly broad, Lim has clearly and consistently built the modern Asian city with his words. Against the rise of starchitects and globalised architecture, he has preached for ethical urbanism and the contemporary vernacular. And while governments increasingly turn to corporations and consultants offering cookie-cutter urban solutions to build their cities, a then 70-year-old Lim started the Asian Urban Lab in 2003, which brings together artists and intellectuals to critically and creatively consider urban life in all its complexities.

Far from being prophetic, Lim has simply been poetic—like his generation of intellectuals in Singapore—in envisioning what their city can and should be. In 1968, Singapore’s then prime minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, declared in a address to university students that, “Poetry is a luxury we cannot afford”[1]. Only a year earlier, Lim had pleaded otherwise when outlining the future of tomorrow’s cities: “We must plan for people and not population, to create places with spatial relationships, not voids between buildings and achieve quality and sophistication, not just pure function,” he said.

“We need poets and visionaries. Poetic reality is all embracing. It takes into account the total personality of every individual.”[2]